Introduction

One of my basic contentions is that in many ways Hamilton embodies something like an echo of the form of Greek tragedy, as we know it from 5th century Athens. Hamilton's effectiveness and popularity stem no doubt from its contemporary hip-hop and rap music, its qualified patriotism, its interest in contemporary hot-button issues of immigrants and immigration, and its reinvention of the founding fathers, who, in contrast to the now common and trite portrayal as stuffy and nearly god-like lily-white figures, are played by actors of color, and are all brought down to earth and made more problematic in various ways.But I would suggest another part of the reason the show is so affecting is precisely that it builds upon the scaffolding of Greek tragedy, either directly, or as tragedy has echoed through the ages, reverberating into Opera and Shakespeare, and eventually into musical theater. And the opening number, "Alexander Hamilton" is a great place to start seeing this in action.

The Greek Tragic Prologue

Greek tragedies typically begin with a prologue. The exact definition is something scholars quibble about; does the word refer merely to the monologue by the first speaker or might it include dialog with other characters? Aristotle, the definitive--but not the first or an infallible--critic, described the prologue as:

ἔστιν δὲ πρόλογος μὲν μέρος ὅλον τραγῳδίας τὸ πρὸ χοροῦ παρόδου

The prologue is the entire portion of the tragedy before the chorus' entrance [parodos].

(Aristotle, Poetics, 1452b)

(Aristotle, Poetics, 1452b)

Only rarely does the play's protagonist deliver the prologue. Sometimes a god begins the play by announcing how they will righteously punish a mortal, as Aphrodite does in the Hippolytus. In the Trojan Women, we see Poseidon grieving the loss of Troy, the city he helped build, and Athena planning vengeance against the Greeks for their violation of her temple. Rather than a god, a few extant plays begin with the protagonist laying out their own story, as Helen does in the play named after her. More commonly, if the prologist is mortal, they are a supporting character. One of tragedy's most iconic prologues is delivered by Medea's nurse in Euripides' Medea:

I wish the ship, the Argo, had never flown

to Colchis through the dark Symplegades;

to Colchis through the dark Symplegades;

that the timbered pines had never fallen

in the vales of Pelion; that the hands of noble men

hadn't rowed in search of the Golden Fleece

for Pelias. For then my misteress Medea

would not have sailed to the towers of Iolcus

struck to the heart with passion for Jason.

(translation by Rachel Kitzinger, in The Greek Plays, Lefkowitz and Romm, eds., 2016)

In those first eight lines, Eurpides has the nurse recap some important elements of the story before the play: Someone (presumably Argos) cut down pine trees on Mt. Pelion and made the ship Argo, which Jason sailed through the Symplegades to Colchis. There Medea fell in love with him and sailed off to his home. Subsequent lines trace the story of Medea's further exploits as it continues up to the plays' present.

In still other plays, the chorus itself introduces the play. Though this may not be a prologue according to Aristotle's definition, it performs much of the same role: introducing the audience to the key players, the relevant background information, and the key thematic concerns of the play. The Persians provides a great example of such a choral prologue which provides thematic info:

"Here are we, the trusted ones

of the Persians gone to the land of Greece

we, guards of the wealthy, gold-decked places

chosen, as fits our age and rank,

by Xerxes himself, our lord and king,

the son of Darius

to steward this land.

but my heart, a prophet of evil, is troubled

over the homeward return of the king

and of the army bright with gold."

(Romm's translation in The Greek Plays, Lefkowitz and Romm, eds., 2016)

of the Persians gone to the land of Greece

we, guards of the wealthy, gold-decked places

chosen, as fits our age and rank,

by Xerxes himself, our lord and king,

the son of Darius

to steward this land.

but my heart, a prophet of evil, is troubled

over the homeward return of the king

and of the army bright with gold."

(Romm's translation in The Greek Plays, Lefkowitz and Romm, eds., 2016)

Even a cursory read over these first ten lines of the play will highlight some of the important thematic elements here: the repetition of the wealth and gold of the Persians, physical manifestations of their hubristic wealth and status, that will be brought low by the defeat of Xerxes by the end. The able-bodied, young Persian men who are "gone," both physically away from Persia in Greece and passed away, died in the war. The foreshadowing builds expectation of the trouble that will accompany the return of the king. Aeschylus prepares us for what is to come using the chorus' opening song.

Tragedy's prologues, then, generally do the following:

- A character (usually not the protagonist) delivers the prologue before the entrance song of the chorus

- Sometimes the prologist is the protagonists' enemy, sometimes their trusted friend, occasionally it is the protagonist themselves.

- The prologist present the background story necessary to understand and contextualize the action of the drama proper

- The prologue introduces the important themes that will resonate throughout the play.

Alexander Hamilton as Prologue

Hamilton's opening number shares a number of similarities with the Greek tragic prologues as I've described them above. If you know Hamilton already, you may have an idea of what I'm about to lay out. If not, I'd encourage you to give the song a listen here:

The title character is nowhere to be seen. Instead, Aaron Burr begins by asking the question that the show's first act will work to answer:

How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a

Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten

Spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor

Grow up to be a hero and a scholar?

(all lyrics are by Lin Manuel Miranda and are taken from the official Hamilton Music site)

As other characters join in to become a chorus more or less in the Greek tradition, what follows is, as in Medea, a recap of the circumstances of the Hamilton's life that led him from his birth to his situation as an immigrant in New York at the beginning of the play. We hear of his role in the trading charter, the hurricane that hit St. Croix in 1772 (and Hamilton's subsequent "writing his way out"), the death of his mother and the suicide of his cousin, and more importantly the collection taken up to send him to New York. When he finally arrives in New York, and announces his name, the prologue (/opening number) is over and the story begins.

The background is hardly filler or incidental. The hurricane will resurface as a metaphor for the gossip that swirls around Hamilton and drives him to publish the Reynolds pamphlet. His talent and drive for the written word are a recurring motif that both reflects the historical Hamilton and aligns him with the prolific hip-hop artists that influenced Miranda. His status as bastard and immigrant and his poverty will drive his marriage, his military commission, and his work ethic.

The "prologue" here is divided among a chorus of the prominent figures in Hamilton's life, his comrades in arms, his love interests, his family, his idol, and of course, the leader of the pack, Aaron Burr, who functions as the show's primary narrator, a kind of anti-Hamilton, a friend and rival. In some ways Alexander Hamilton eschews the tradtional Greek model of a single character delivering the background. Instead, the all do, functioning simultaneously as the interested parties who might deliver that prologue in a play like Medea and the chorus like that of the Persians.

The background is hardly filler or incidental. The hurricane will resurface as a metaphor for the gossip that swirls around Hamilton and drives him to publish the Reynolds pamphlet. His talent and drive for the written word are a recurring motif that both reflects the historical Hamilton and aligns him with the prolific hip-hop artists that influenced Miranda. His status as bastard and immigrant and his poverty will drive his marriage, his military commission, and his work ethic.

The "prologue" here is divided among a chorus of the prominent figures in Hamilton's life, his comrades in arms, his love interests, his family, his idol, and of course, the leader of the pack, Aaron Burr, who functions as the show's primary narrator, a kind of anti-Hamilton, a friend and rival. In some ways Alexander Hamilton eschews the tradtional Greek model of a single character delivering the background. Instead, the all do, functioning simultaneously as the interested parties who might deliver that prologue in a play like Medea and the chorus like that of the Persians.

Thematic Set-up

Like the Greek tragic prologues--and, to be clear, like many other Broadway musicals--Alexander Hamilton introduces the themes that will continue to resonate through the show. Some of the key themes to which I expect to return include:- Writing his way out: Just as it is Hamilton's literary description of the hurricane that secured his exit from his island, Hamilton will repeatedly use the power of the pen to achieve his goals. The prodigious volume of his work is clearly both a subject of fascination and an inspiration for Miranda. The founding fathers were a prolific bunch and Hamilton stands out amongst them for the quantity and quality of his writing. But more importantly, perhaps, that writing becomes the source material for the play itself, and thus the character of Hamilton is shown trying to write his own legacy.

- Kleos: Over and over, Hamilton is driven by his future place in the history books. His conversations with Aaron Burr and, even more, George Washington are dominated by the theme. This obsession with how one will be remembered is a remarkably profound echo of the concerns of Homeric Heroes like Achilles, who chooses an early death at Troy with the understanding that it will grant him kleos, glory. In the opening number, the chorus sets up the show to in some ways (re-)define Hamilton's legacy, by posing the questions: "Oh, Alexander Hamilton (Alexander Hamilton)

When America sings for you

Will they know what you overcame?

Will they know you rewrote the game

The world will never be the same, oh"

Later on they suggest a pessimistic answer:

His enemies destroyed his repAmerica forgot him

Hamilton's reputation, therefore, rests in the hands of the actors on stage and the audience there to see the play. His success in re-gaining lost kleos is in our hands.

- Metatheatricality: The actors acknowledging the theatrical construct of the play is not a concept that one often sees in Greek tragedy. (Though there are subtler winks at the artificiality of drama). Rather this technique is more native to Greek comedy, which regularly, or more accurately, structurally breaks the fourth wall and engages the audience directly. The show's audience, of course, is the "they" in the lines quoted just above, and the chorus highlights the metatheatricality as the cast of important figures in Hamilton's future life sing him the metaphor: "We are waiting in the wings for you." The lyric works metaphorically on a literal level (they will literally exit stage and wait in the wings for their entrances to interact with his character) and works literally on a metaphorical level (their interactions are imminent in the story of Hamilton's life). The relationship between the play and the story is one frequently evoked and that helps define a unique position for the audience not as observers of Hamilton's story, but rather as spectators of the play Hamilton and therefore as people implicated in the story that play tells.

- "Tragic Flaw"s-- The idea of the "tragic flaw" is based on a misunderstanding of Aristotle's poetics. Still the idea that a tragedy turns around a mostly good character with one critical failure is a prominent idea that is connected in the popular idea with Aristotle and his reading of Greek tragedy. Given all that, it is striking that the chorus lays out a clear set of flaws for the tragic figure of Hamilton:"You could never back down,

You never learned to take your time!"

Thinking Back

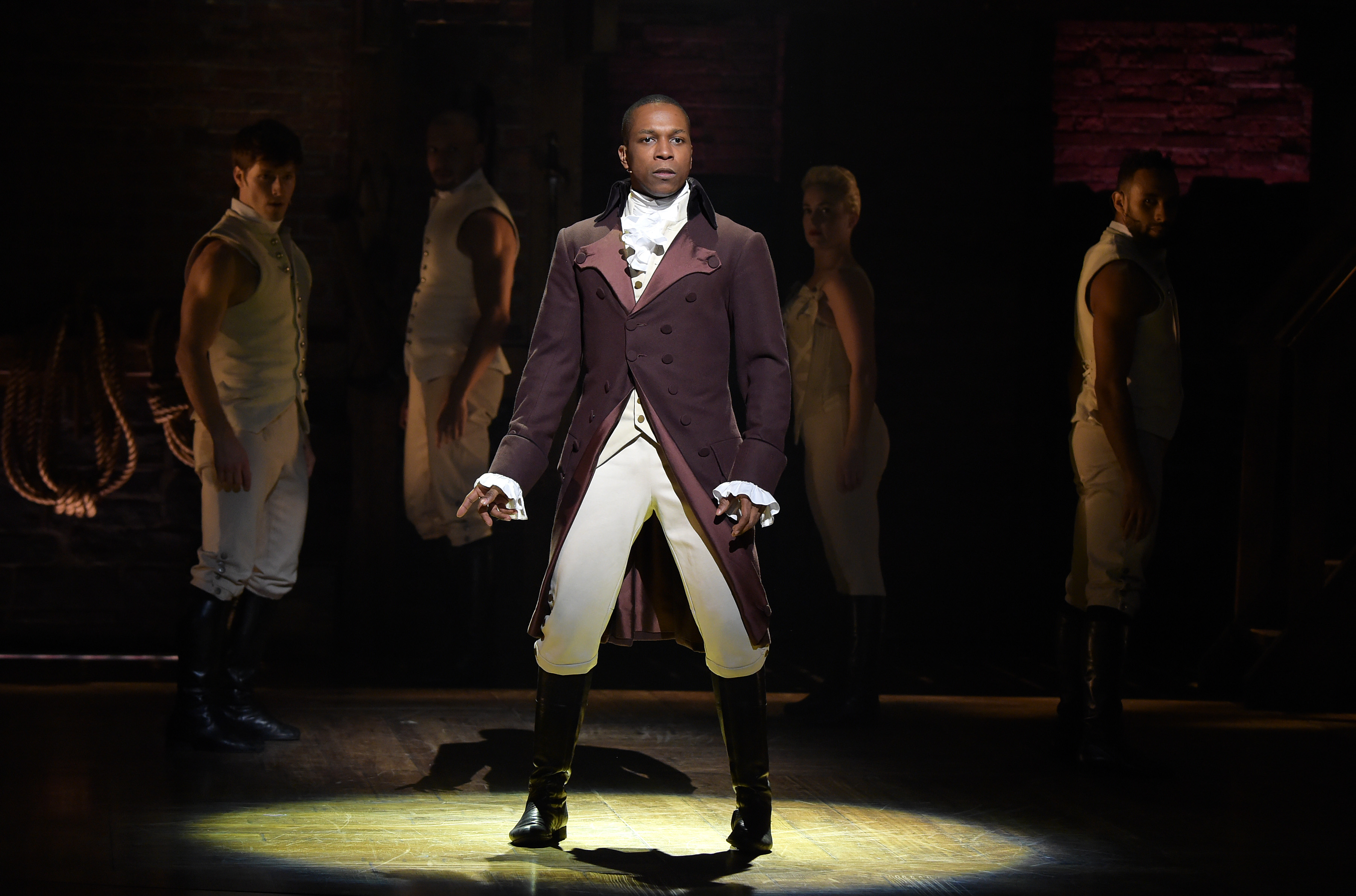

There're also some interesting moments that are rich with food for thought on the way in which an understanding of a contemporary Broadway musical like Hamilton might give us creative insight into potential ways of understanding ancient performance. These include:- Rhythm and Poetry: After a brief fanfare, the opening lyrics take place in front of minimal orchestration. Leslie Odom Jr. asks the opening question in a calm rhythmic delivery against minimal orchestration: a chord or two and snaps from the stage. Miranda is a master of rhyme and poetic schemes--See this wonderful demonstration from the Wall Street Journal. Every line of every Greek tragedy was a poetic line driven by rhythm rather than rhyme but as cleverly crafted and sometimes playful and this is hard for us moderns to appreciate even in Greek, and hopelessly out of reach even in the best translations. As I teach tragedy, I ask students to think about moments like this to reflect on how an artfully crafted piece of poetry differs in its effect from the stage compared to more prosaic language. While Miranda's tricks are different than, say, Aeschylus' both are masterful deployers of their language, and indeed the power of both their works stems from the language as much as the content.

- Localization: The fact that Hamilton is set firmly in New York City makes sense given some key moments of Hamilton's life, but of course it also corresponds with the physical setting of the play's venue, and it allows the historical play to respond to and comment on ideas about the polis in which the audience members are either living or acting as tourists. When the company sings (and repeats)"In New York you can be a new man (Just you wait)In New York you can be a new man (Just you wait)In New York you can be a new manIn New York, New YorkJust you wait!"

they are referring both to the way New York provided Hamilton an opportunity for reinvention, and the way it has for those who have moved and continue to move there to make their fortunes or be a new person. Almost all the extant Greek plays we have were written in Athens by Athenian writers for an audience that was primarily (though definitely not exclusively) Athenian. Athens is sometimes represented on stage as a setting, but more often is represented in the person of the mythical king Theseus, a mythologized founding father of Athens, whose presence in a play always implies some commentary about the contemporary city where the play was being performed. Hamilton may let us think in a different way about the performative effects of the evocation of the place of performance in Greek. - Lin-Manuel Miranda is a rather rare example in the modern theatrical world of an author of a major play who is also the star and title character. The opening number builds in space for him to make a grand entrance well after the song's opening chords. He first appears and defines his role, in response to Aaron Burr's question "What's your name, man?".. Miranda responds "Alexander Hamilton" before pausing for the inevitable thunderous applause for the leading actor and then repeating "My name is Alexander Hamilton." It's not entirely clear, but it seems that the playwright of ancient plays may have played the protagonists at times too. It's tempting to imagine that Aeschylus' infamous tactic of bringing a character on stage and then withholding their first line to create anticipation might have been a similar strategy for playing with audience desires and tensions.

- Burr as Narrator/Antagonist/Tragic Hero of his own. Burr's role in the play is complicated, too complicated to expound upon extensively in what's already a long post. But a few thoughts:

1.) Burr tells the story of Hamilton and is Hamilton's greatest rival. As Miranda has made clear, this is in some ways an homage to having Andrew Lloyd Weber's tradition of having the antagonist tell the story. Judas tells the story of Jesus (and becomes a sympathetic figure in the process). The everyman Ché tells the story of Evita Peron, as she steps on him to ascend to her glory. This then is a musical theater trope and a response to the trends of the genre itself.

2.) Burr in many ways is set up as a kind of rival tragic figure to Hamilton. The story is as much Burr's as Hamilton, and whereas Hamilton achieves a kind of heroic apotheosis, it is Burr who is irredeemably brought low by his act in the play. This, I think, builds on Greek tragedies, like Medea, in which there are indeed multiple tragic heroes, Medea and Jason. Burr's status as antagonist (and counter-hero) is sealed at the end of the song, as the characters identify their relationships with Hamilton and Burr quips "And me? I'm the damn fool that shot him." - Telling a Well-Known Story. Although Burr's killing of Hamilton in a duel is history of over 200 years, and indeed is one of the only things many people know about Hamilton (see the famous "Got Milk" ad above), to some it has evidently come as a shock

Telling a fairly well known "historical" story in a new way for audiences with differing familiarity with the source material is something Greek playwrights did in (almost) every tragedy. The mythological material from which almost all tragedies drew was seen as, in most cases, at least quasi-historical, and yet people did not expect Historical Truth (tm) from the stage. Playwrights could play with the story, alter details, add characters, tweak motivations so long as the basic story stayed the same. Medea has to kill someone in revenge for Jason's re-marriage, but it could be just the wife, or it might be the wife and her father, or it might be the kids. In the same way, Hamilton has to end with Burr killing Hamilton in a duel; that's the constant. But how and why and with what intent, that's the play..@Lin_Manuel one fav moment @ #WesHam:Burr: "..and I'm the damn fool that shot him."Woman next to me: GASPS LOUDLYMe: *did you not know?"

— Carolyn Dundes (@spiffyscientist) October 4, 2015

Okay, so that's it. In future I'll be returning to many of these ideas and themes, but for now, on we go!

Further Reading:

In writing this piece, I came across the following which may be of further interest:

- Melanie Bettinelli's piece, "Hamilton: an American Tragedy" engages with the idea of Hamilton as a tragedy and focuses on the idea of catharsis

- Phoebe Corde's piece on the character of "Bullet" who relentlessly pursues Alexander throughout the play, "The Piece Of Foreshadowing In 'Hamilton' That Everyone Misses"

Comments

Post a Comment